Thursday, July 16, 2020

My video documentary about Will Vinton and Claymation

Saturday, May 16, 2020

The incredible true story of Jeff, the one-legged drummer

Jeff and I were classmates in the education program at Lewis and Clark College in the fall of 1983. I was working toward a secondary English teaching certificate; Jeff was in the deaf education program. One day after ed psych, I approached Jeff and introduced myself. He stuck out his hand, told me his name, and invited me to join him for coffee at the student lounge across campus.

We were soon friends, and after a few meetings outside of class we learned that we had something else in common besides the ed program: we were both drummers. When I asked Jeff if having a fake left leg made drumming difficult, he said it wasn't really a problem because it was just his hi-hat foot, and operating the hi-hat pedal wasn't that difficult.

Eventually I felt we were good enough friends that I could ask him how he'd lost his leg. His answer was the stuff of nightmares.

One spring evening, Jeff told me, when he was an eighth grader at Western View Middle School in Corvallis, Oregon, he and some friends found a ladder propped up against an outside wall of the school and decided to climb up on the flat roof. Once on the roof, they thought it'd be fun to do something they'd heard was popular with college kids and adults: streaking. Taking off all one's clothes and running a short distance, preferably without getting caught.

So Jeff and his friends took off all their clothes and streaked across the roof of Western View Middle School.

Unfortunately, the not getting caught part didn't turn out so well. Unbeknownst to the streakers, a teacher was working in his classroom late that evening and heard the commotion on the roof. The teacher went outside and started circling the building to see if he could find the source of the noise. When he spotted the streakers, he yelled at them, "Hey you kids, come down from there!"

Rather than heading back toward the ladder to climb down and turn themselves in, Jeff and his friends decided to run toward a side of the roof where they thought they could jump off and run away. Jeff was the first to jump off.

He was also the last to jump off.

As he was falling toward the ground, some twist of physics or fate conspired against him and threw him backwards, toward the side of the building. And there, unfortunately, on that particular side of the building, was a big plate-glass window.

Jeff fell backwards through the window, shattering the glass—and slicing his left leg almost completely off.

"Your shock and pain must've been horrific," I said to Jeff.

"Almost as bad as my embarrassment," he replied. "Remember, I was naked."

Oh, yeah. Naked. And bleeding to death.

Jeff and his mostly severed leg were rushed to the hospital, where surgeons determined that the leg was too damaged to reattach. He would need a prosthetic.

Ten years later, Jeff was enrolled in the education program, aiming to become a teacher of the deaf. I, on the other hand, was looking toward a new career (following my three-year stint as production manager for Claymation film producer Will Vinton) as a secondary English teacher.

After we finished our respective programs, I landed a position teaching English and U.S. history at Highland View Middle School in Corvallis—the home of Western View Middle School, where Jeff had lost his leg. Jeff, meanwhile, found a job in Portland. When I informed him I was now living in his hometown, he said he'd come see me next time he was in Corvallis to visit his parents.

A few months later, when Jeff came to see me at my new home, I finally got a chance to see how he was able to play the drums. He was pretty good, and it appeared to me that his fake leg didn't hinder his hi-hat prowess one iota. In fact, after seeing him play with that leg, I decided to practice a bit more so as not to be outplayed by a monoplegic.

Jeff and I got together one or two more times after that, and then we lost touch with each other, likely because of our respective jobs, relationships, and the physical distance between Corvallis and Portland.

A few years later, I was one of several teachers chaperoning a weeklong trip to Washington D.C., with 64 Corvallis eighth-graders. One of the other teachers, Chuck Wenstrom, happened to teach history at Western View Middle School. I told him I knew a guy who, when he was an eighth-grader at Western View, went streaking with some friends on the school roof one night and lost a leg when he jumped off and fell backward through a window.

I was completely unprepared for Wenstrom's reply. "I was the one who told Jeff and his friends to come down off the roof," he said. "But I didn't mean for them to jump off. They were supposed to climb back down the ladder they used to get up there. You can't imagine how badly I felt about Jeff losing that leg."

He was right: I couldn't imagine. And neither of us could imagine how Jeff felt.

I'll never forget Jeff's kind face and easy smile, and I'll always wonder whether they were, at least in part, a product of the pain he had to endure and the obstacles he had to overcome as a result of his accident. If so, it was perhaps the best possible outcome of one of the worst imaginable tragedies.

Jeff, wherever you are and whatever you're doing, I wish you happy trails. On safe ground. With your clothes on.

Saturday, May 2, 2020

That time I fell off a ski lift

I used to—until it happened to me.

I was 18 and a freshman in college. In fulfillment of my "Physical Education" requirement, I had enrolled in a downhill skiing course, which consisted of eight weekly lessons, every Saturday, on the slopes near Timberline Lodge on Mt. Hood.

At over six feet tall and with unusually long legs and a short torso—in other words, a high center of gravity—I'm not well built for skiing. But for the first five weeks of class, I held my own and managed to keep from falling or doing anything terribly embarrassing. I usually skied with my dorm RA (resident assistant), Ron Starker, a nice guy with a good sense of humor and a great laugh. We were friends then and still are today. (You'll soon understand why I felt it important to establish that up front.)

On the sixth Saturday, Ron and I were riding the ski lift together, as usual, and looking forward to skiing on our own for a change, without the instructor. The instructor had told us she thought we were good enough to take on one of the more challenging slopes by ourselves, and we were determined to prove her right.

As the ski lift approached the jump-off point, Ron and I got ready to exit our chair and set off on our adventure. But then something happened. As Ron stood up and dismounted the chair, the chair bounced back up and smacked me in the butt, causing me to lose my balance just as I was trying to dismount. I remember seeing Ron ski off to safety as I was tumbling backward and down, down, down into the snow-lined depression around the base of the massive steel turnaround pylon.

I landed on my back in the snow—just enough snow, apparently, to break my fall and not my back. I wasn't sure if I was dead or alive, but my eyes were open and I could feel my limbs, so I figured there was a good chance I had survived the fall, although I wasn't sure how.

The ski lift stopped, and frantic faces started appearing all around the rim of the pylon hole, peering downward at me. One of them asked if I was OK, and I said "I think so." I really wasn't sure, because I had, after all, FALLEN OFF A SKI LIFT. Do people survive such things?

Within what seemed like seconds, the Ski Patrol showed up. (Ironically, just two years earlier my rock band had played a Ski Patrol benefit dance at Timberline Lodge. Maybe these guys were among the attendees—and beneficiaries?) Within a few more seconds, they somehow managed to send a couple of guys down into the hole with a stretcher, strap me onto it, and hoist me up to the surface. I told them I felt fine, but they wanted to make sure I hadn't broken anything or suffered a concussion or internal injuries. So I waited patiently (what else could I do?) while they checked me over...and over...and over, with two dozen faces—including Ron's—peering anxiously down at me.

And with the ski lift motionless above me, full of people wanting to get started skiing.

It was excruciatingly embarrassing.

Finally deemed intact, I was released from the stretcher and got back on my feet. I think there was some applause, but I'm fuzzy on the details after this point because I was 100% focused on just getting the hell out of there. I strapped on my skis, nodded to Ron that I was ready to go, and off we went toward the slopes.

The easy slopes.

|

| A Timberline Lodge skier who probably didn't fall off the ski lift. (Photo: tripadvisor.co.uk) |

Tuesday, March 31, 2020

My Claymation ad

To my knowledge, we never received a single call in response to this ad. However, within a few years, Vinton was doing virtually nothing but TV commercials (California Raisins, M&Ms, etc.). Maybe it was just a delayed reaction? : )

Saturday, March 28, 2020

Susan Orlean and me

I called Ms. Orlean and set up a time for us to get together for lunch at a popular Northwest Portland restaurant called The Wheel of Fortune (later renamed Ezekiel's Wheel, probably to avoid copyright infringement). I had no idea what Ms. Orlean wanted to talk about, but I was game for anything.

Anything, that is, except what she ended up wanting to talk about: skeletons in Will's closet.

She wanted dirt.

It wasn't that I was unaware of such skeletons or dirt (although the few examples I was aware of were relatively benign); it was that I was unwilling to help this ambitious and assertive young muckraker to tarnish my boss's—my friend's—reputation, for the sake of bolstered newspaper sales or a Pulitzer (ha ha).

So I was a bit peeved when Ms. Orlean's intent became clear, and matters were not improved when, after we had finished lunch, she looked at me expectantly and said, "I'm not sure how these things work; do you pay, or do I, or...?"

Me, pay? I thought. For an interview you requested?

I managed to utter something about how maybe Dutch would be best, and she reluctantly agreed. I guess in those days Willamette Week didn't pay its hungry young writers very well. We paid our checks, said our goodbyes, and that was the last I ever heard from her. And no story about Will ever appeared in her newspaper. I guess since I hadn't given her what she came for, she decided not to write anything. Which was fine with me.

When I got back to the office and related my experience to Will, he just smiled and said, "Ah, one of those."

Two decades later, I'm driving down I-5 and listening to NPR. Susan Orlean is on, reading an excerpt from her nonfiction book, Saturday Night.

She's good. Her book sounds good. No skeletons, no dirt. She's destined for greatness, I think, shaking my head and smiling to myself.

Maybe I should've bought her lunch?

|

| Susan Orlean |

Friday, March 13, 2020

My trip to the Academy Awards

He was right.

We finished the film in late 1978, and immediately started sending it out to film festivals around the world. It won at least a bronze and sometimes a silver or gold in virtually every one. Then we screened it at a theater in Los Angeles just before the December 31 deadline to qualify it as a potential Academy Award nominee (still a long shot, I thought)...and waited.

Nominated!

On February 20, 1979, James M. Roberts, the Executive Director of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, sent Will a telegram notifying him that Rip Van Winkle had been nominated for an Academy Award.I was, as Will predicted, blown away.

|

| A scan of a photocopy of the telegram Will Vinton received notifying him that our Claymation short film Rip Van Winkle had been nominated for an Academy Award. |

Cool. Except for one thing: there were not six, but seven of us (besides Will and Susan) who wanted to go to the Academy Awards. We would have to draw straws.

As luck would have it, I drew the short straw. I would not be going to the Academy Awards. Booo!

However, fate had another idea in store for me: after pondering for a few days whether he really wanted to attend the Awards, animator Barry Bruce decided against it. He would sell me his ticket. At cost.

I was in eighth heaven. I had watched the Academy Awards ever since I was a kid, but I had never dreamed of attending—and now I was not only going to attend, but I would be there as a member of the crew that had produced a nominated film. I couldn't even wrap my 23-year-old brain around such an incredible stroke of luck.

Then reality started kicking in. As a recent college grad with bills to pay and a student loan to start paying off, I didn't have much disposable income. I would have to come up with about $200 more to help me cover the tux rental, plane ticket, hotel room, and food. I decided, against my better judgment, to ask my conservative (read: frugal) parents, who had rarely, if ever, lent money to any of their four kids. Fortunately, they were almost as excited as I was about this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, and they agreed to the loan. I was on my way.

|

| A scan of a photocopy of my ticket to the Academy Awards. |

Not a chance. I decided against renting a black tux. Instead, I rented a brown one.

Big mistake. I failed to consider how conspicuous I might feel, being the only guy at the Academy Awards not wearing black. But for the moment, at least, I was reveling in my token act of rebellion.

Hollywood!

We all decided to stay in the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel, which had been the site of the first Academy Awards, in 1929. It was old and rustic and the beds were uncomfortable, but we liked the history—and the relatively low rates. Music composer/producer Bill Scream (his "professional" name) and I shared a room.The night before the Academy Awards show, Will arranged for some of us to join the producers of another nominee in the Animated Short Subject category, Special Delivery, for drinks at the Beverly Hills Hotel, a faux classy old pink building. Accompanying the Canadian producers of the film, Eunice Macaulay and John Weldon, was Marshall Ephron, the former host of a satirical TV show called The Great American Dream Machine, which I used to watch on Oregon Public Broadcasting (our local PBS station). Even though these folks were "the enemy"—one of our two competitors for the Oscar—we got along famously (almost famously?) and enjoyed their intelligence, wit, and graciousness. We decided not to hate them if they won.

The next morning, Will, Bill, and I drove to the house of an animator friend of Will's, John David Wilson (who had animated the opening credits for Grease) and his wife, Angel. After a pleasant but otherwise uneventful visit, Bill declared to me on our way back to the car that he was in love with Angel—who was, admittedly, quite angelic. But married. (Sorry, Bill!)

The Academy Awards!

Once back at the hotel, we all got dressed in our tuxes and then met outside by the pool for a photo. The driver of the limousine was kind enough to take a moment and shoot this goofy snapshot just before we all piled into the limo (yes, all eight of us) and headed across town to the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, where the Awards ceremony would be held. |

| Left to right: Executive Producer Frank Moynihan (of Billy Budd Films, New York), his wife Annie, music composer/producer Bill Scream, animators Don Merkt and Joan Gratz, screenwriter (and Will's wife at the time) Susan Shadburne, Will, and 23-year-old me (in total shock and awe). Not in attendance: animator Barry Bruce and music composer Paul Jameson. (Photo by limo driver) |

|

| Will Vinton and his wife, Susan Shadburne, just prior to the 1979 Academy Awards ceremony. (Photo by Rick Cooper) |

And the Winner Is...

A Few More Stars

Back to Reality

Wednesday, February 19, 2020

Will Vinton: The King of Clay Animation

Will Vinton and His Animated Shorts

Hi Rick,

I'm working on an obituary about Mr. Noyes. I read your fabulous journal article about animation and wanted to make sure I described you correctly. Is this right: "Rick Cooper, a former production manager for Will Vinton Productions, a claymation film company, wrote in the journal Design For Arts in Education."

Please let me know. And thanks. Mike

I replied:

Hello Mike,

Yes, that is correct—and thank you for asking. Wow, I can’t believe someone actually read that article. : )

Thanks for the blast from the past!

Cheers,

Rick

...and he replied:

It was fascinating! Thanks for getting back to me.

If you subscribe to The NY Times you can see a quote attributed to me in this obit for clay animator Eli Noyes: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/03/arts/television/eli-noyes-dead.html

I’m in the Times, therefore I am? : )

Rick

The Oscar Built of Clay

I knew immediately whom I wanted to interview. As a huge fan of the locally produced clay-animated short film Closed Mondays, which I'd seen several times at The Movie House in downtown Portland, I had been looking for an excuse to meet the film's producers, Will Vinton and Bob Gardiner. Now, thanks to Mr. Whetmore, I had that excuse. And I could use my status as a writer for the college student paper, The Pioneer Log, as my "press pass."

Then I learned that Closed Mondays had been nominated for an Academy Award for best animated short subject. Damn, I thought. Now it'll be impossible for me to get an interview with these local celebrities. They'll be swarmed with interview requests from all the papers and magazines.

Nevertheless, I decided to give it a go. I found Vinton's phone number in the Portland phone directory, called him, and asked whether he would be open to an interview. Miraculously, he said, "Sure," and suggested we meet for lunch the following week at his office in Northwest Portland.

I couldn't believe my luck. Here was this semi-famous filmmaker, who might be on the verge of winning a freaking Oscar, agreeing to an interview with some 19-year-old college punk who may or may not be able to write—and definitely wouldn't be getting his article published, considering all the competition by professional journalists with actual credentials and connections to actual publications.

After Vinton and I met, I typed up a draft of the article on my manual typewriter, shared the draft with Vinton in person at his home in the Northwest Portland hills (where Vinton and Gardiner had shot Closed Mondays), took notes as Vinton suggested a few changes, and then went home and typed up a new draft incorporating the edits.

I sent the article to the first publication I could think of that might be interested: Northwest Magazine, which was the Sunday supplement to Oregon's biggest newspaper, The Oregonian. Considering that the magazine had a purported circulation of around 400,000, this was an extreme long shot for a first-time writer. I was certain the editor would read the first sentence, laugh uproariously, make several paper planes out of my article, and gleefully fly them all into the nearest round file.

Fortunately, another long shot came through for me: Closed Mondays won the Oscar. The next day, the editor of Northwest Magazine called me and said he wanted to publish my article, but could I please get a few more quotes from newly minted Oscar winners Vinton and Gardiner and add them somewhere near the end of the article? Oh, and maybe take a photographer to Vinton's house and get some nice black-and-white stills? There would be $75 in it for both me and the photographer.

"Um, sure," said the starving college student, while wetting his pants because his very first article was going to be published—in none other than Oregon's biggest magazine in Oregon's biggest newspaper.

There's more to the story (isn't there always?), but I think that's enough ado for now. Here's the article. (Apologies for the poor-quality scans and obvious seams—all DIY by yours truly, who accepts all the blame.)

Tuesday, February 18, 2020

Claymation: Making Movie History with Mud & Magic

My writing here is embarrassingly amateurish and the editing a bit sloppy (typos and inaccuracies), but I'm going ahead and publishing it here anyway for, um, posterity. My sincere apologies to anyone I might offend in the process...

Tuesday, February 11, 2020

Robin Trower and me

|

| Portland band Morning After (1973-78; image courtesy of Bob Stull, GuitarCrazy.com) |

Flash forward three decades, and my wife and I are dancing to Robin Trower live, on a stage right next to the dance floor, in a small venue in Albany, Oregon. It was a Sunday in May—Mother's Day, in fact—and I believe we had paid $14 each for our tickets. Trower played all his greatest hits, including "Day of the Eagle," "Daydream," "Too Rolling Stoned," and "Bridge of Sighs," and we had the best Mother's Day ever (speaking strictly for myself, of course).

A few years later, in February of 2008, I attended another Trower concert, with my brother and a friend, at the Roseland Theater in Portland. Trower again played all my faves, and my socks were again knocked totally off. Trower was in his 60s at the time, and he could still rock like the 20-something arena rocker he became after the release of Bridge of Sighs.

My brother had to head home right after the concert, but my friend, a guitarist who had previously spoken with Trower following other concerts, wanted to chat with Trower again about some sound-effects pedal setup or something. There happened to be a meet-and-greet happening downstairs after the show, so we headed down there and got in line.

Trower was there within minutes after the show ended, and started enthusiastically signing albums, CDs, T-shirts, and all other manner of concert and tour memorabilia, while chatting cordially with his fans. We finally made it to the front of the line, and I had Trower sign my wife's ticket stub from a Trower-Tull concert she had attended in LA back in the mid-70s. I told him Jules had been wanting to get it signed ever since that concert, and Trower replied, "Well, tell her thanks for waiting so long!"

I thought that would be the end of it, but after my friend was done talking to Trower, Trower's manager invited my friend and me to pose with Trower for a photo. Nobody had a camera, so the manager guy borrowed my cheap little flip phone to take the shot. Unfortunately, the picture is too fuzzy to be recognizable, even if you squint really hard and use your imagination, so I won't bother sharing it here. I will, however, share a YouTube video of Trower performing "Day of the Eagle" and "Bridge of Sighs" back to back at a 2005 concert in Germany. Enjoy!

Saturday, February 8, 2020

Dallas "Gumby" McKennon and me

|

| Dallas McKennon (source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dallas_McKennon |

I remember McKennon, who was about 60 at the time, as a kind, jovial fellow with a ton of talent and energy. He was fun to watch in action, insisting on doing as many takes as necessary to get the parts right. I admired his professionalism, and liked him a lot personally. He seemed to like me, too, because following the recording/filming session, he extended an open invitation to me to visit him at his home in Cannon Beach, on the Oregon coast.

About a year later, I was living in Tolovana Park, just south of Cannon Beach, and had invited some people over for a Claymation film showing. I had borrowed a 16mm projector from a local school, but for some reason the projector was missing the takeup reel—and there was no way to show the films without one. Immediately I thought of McKennon: with all his experience in film, he might have a spare reel he could lend me.

So, audacious jughead that I am, I found McKennon's number in the phone book, called him, and asked if he happened to have a 16mm takeup reel. He said he was pretty sure he had one lying around somewhere, and if I wanted to come get it he'd go look for it and have it ready for me when I arrived. Ten minutes later I was at the front door of McKennon's house—a beautiful, two-story contemporary with massive picture windows facing the iconic Haystack Rock—and he was there to greet me, takeup reel in hand.

I know it's silly to idolize celebrities, to imagine that they are somehow more special than the rest of us, but here was this guy I had grown up watching/hearing on some of my favorite TV shows, taking time out of his busy day to do a virtual stranger this odd little favor. I was not just extremely appreciative, but maybe a little weak in the knees—and struggling not to show it.

I said thank you; he said you're welcome and invited me to call again anytime; and I was on my way, takeup reel in hand, a smile on my face, and the Gumby theme song in my head.

Wednesday, January 29, 2020

Claudia Weill, Claymation, and me

Nevertheless, for some reason Claudia Weill wanted to see Claymation, and she wanted to meet one of the people who worked on it. Despite my being merely a production assistant on the film, Will asked if I would do the honors. Having seen and liked Weill's movie, I eagerly agreed.

Weill was going to be in Portland for a publicity tour stop, so I set up a private screening for that date at a movie theater near the studio called Cinema 21.

On the arranged date and time, I met Weill outside the theater, and we went inside to find seats (an easy task, since we were the only ones in the theater). Oddly, Weill chose to sit behind me rather than next to me. I didn't take it too personally, however, as I knew she was a big shot and I was just a lowly production assistant, somewhere between "best boy" and "key grip" in the film credit hierarchy.

|

| Claudia Weill (source: https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0918041/mediaviewer/rm527654400) |

Her answer took me by completely by surprise.

"There was no mention of Eli Noyes anywhere in the film. His Clay or the Origin of the Species was where it all started, was it not?"

I was flummoxed. Speechless. Of course I'd heard of Noyes' groundbreaking clay-animated film, which was nominated for an Academy Award in 1966. But our film was specifically about Claymation, a style of clay animation exclusive to and trademarked by Will Vinton Productions. It was not—and didn't pretend to be—about clay animation in general. I couldn't believe Weill had chosen to attack our film because it was about our work and not Noyes'—nor anyone else's. Was she joking? Jetlagged? In a crappy mood because of all the traveling she had to do to promote her film?

I struggled for an appropriate response. "Um...uh...well, this film is about our particular brand of clay animation, which we call Claymation. If it were about clay animation in general, we certainly would've mentioned Noyes' work."

Weill wasn't satisfied. "Eli Noyes happens to be a friend of mine, and his film broke the ground upon which you're making your films. I would've thought you might mention him, at least."

Before I could come up with another stumbling, half-assed reply, Weill got up, thanked me for my time, and left the theater.

I guess she hadn't been impressed.

But then, neither was I. Weill might've been a decent filmmaker, but in my opinion she fell a little short of being a decent human being.

When I told Will what had happened, he shook his head and muttered something about prima donnas. And he, too, was incredulous that Weill thought Claymation should've mentioned Noyes.

Two years later, however, when Will commissioned me to write a book about Claymation, I remembered my run-in with Weill and decided that, rather than risk pissing her off again, I would be sure to mention Noyes and his film. Here's what I wrote:

...in 1965, a film student named Eli Noyes, Jr. resurrected clay briefly in a short film called Clay or the Origin of Species, a kind of time-lapse rendition of evolution with creatures metamorphosing and evolving in assorted outrageous ways. Although relatively basic in style and execution. [the film] was a respectable effort, serving as a bulldozer for greater works.Oh, and I found his film on YouTube:

Happy now, Ms. Weill? : )

Part one of a two-part YouTube video of Claymation:

Part two (featuring my face in clay at the end—I'm the one with the long hair and mustache):

Monday, January 27, 2020

Ornella Muti, the Ovulation Method, Frank Fink, and me

Further, I never would've known who Ornella Muti was, if not for my German housemate, Frank Fink, who spotted my box of books addressed to her and recognized the name.

"Ornella Muti?" he said. "The beautiful Italian actress? What are you sending her?"

"Italian actress?" I said. "I had no idea. She ordered some Ovulation Method books from me."

Frank looked at the address on the label. "A hotel in Chicago? What's she doing there?"

"I dunno," I said. "Maybe making an American movie?" (In retrospect, my guess might've been right: a movie starring Ornella Muti, Oscar, was shot in Chicago around that time.)

"Why does she need so many Ovulation Method books?" Frank asked.

"I dunno. Maybe they're for her and nine of her friends?"

"Wow," Frank said. "Every guy I know in Germany is in love with Ornella Muti."

"Want me to add a note to my box asking for an autographed photo?" I asked.

"Sure!" Frank said.

So I did. And Ornella Muti sent me an autographed photo, inscribed to Frank.

It made his day.

|

| Ornella Muti in 2000. (Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ornella_Muti) |

Thursday, January 23, 2020

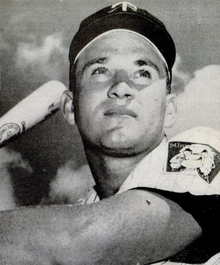

Our piece of art by Mrs. Harmon Killebrew

|

| Harmon Killebrew in 1962 (source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harmon_Killebrew) |

The artwork, a sort of shadowbox painting of an old barn in the snow, appealed to us because it reminded us of barns we'd seen around our rural neighborhood. We also liked the technique, which gives the appearance of depth as it was rendered on three successive panes of glass, and the frame, which was fashioned from old barn wood. At just $10, it seemed like a low-risk, high-reward investment.

|

| Our piece of art by Elaine Killebrew (1977) |

A quick Google search gave us our answer: Elaine was the ex-wife of baseball great Harmon Killebrew. But just to be sure this was the same Elaine, we decided to do some more checking. Jules found one of the adult Killebrew children on Facebook, and I found another one on Twitter. Both confirmed that the piece was, indeed, their mother's. But just to be absolutely sure, we did some more checking online, and found a digital copy of a check written in 1981 from Harmon to Elaine and endorsed on the back by Elaine. The signature on the painting appears first below, followed by the check. Jules and I are no handwriting experts, but these signatures sure look like a match to us.

Wanting to know whether the artwork had any monetary value beyond the $10 we paid for it, Jules emailed all the information we had about it, plus the images seen here, to Antiques Roadshow sports appraiser Leila Dunbar. Dunbar replied that, because she deals primarily with sports memorabilia associated directly with the athletes themselves, not their spouses, she would feel uncomfortable offering us an appraisal.

We're fine with our little treasure having only intrinsic value to us. However, we're still interested in finding out, if possible, whose barn is depicted in the piece, and where it's located. Any guesses?